The Beauty of Chess

The Beauty of Chess

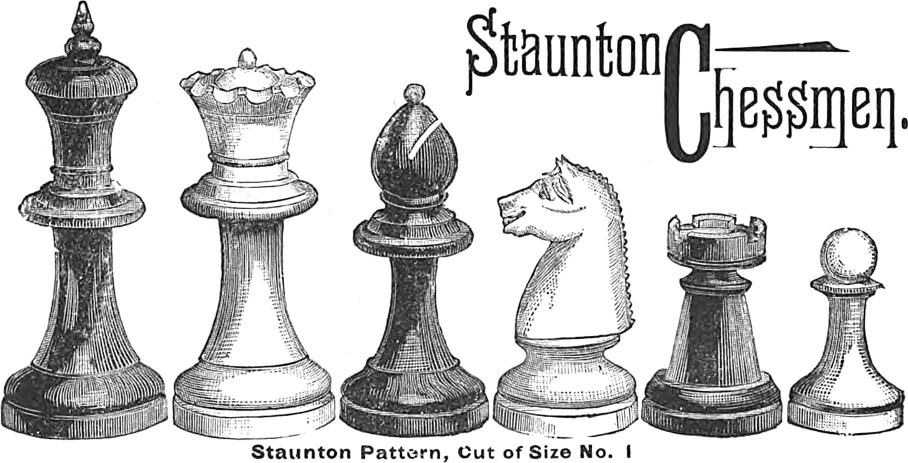

Chess pieces are miniature works of art that have accompanied players since the game's inception. The dominance of the Staunton design, which became standard after FIDE's founding in 1924, has unfortunately overshadowed the artistic diversity of earlier chess sets. All the more reason to take a closer look … The page is a bit long, but hopefully it's worth scrolling through. And by the way: Staunton pieces from the 19th century are absolutely wonderful, that is undisputed.

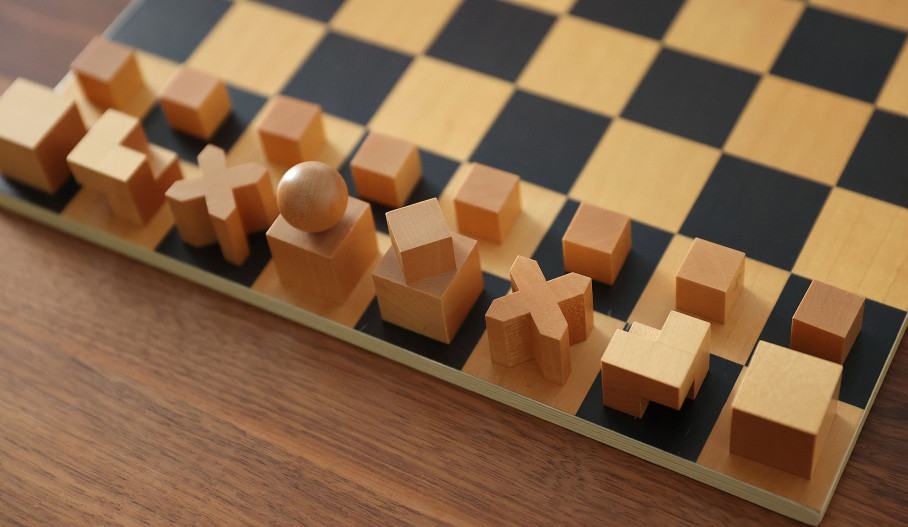

Helfried Puhr calls the chess pieces he designed and manufactured in his workshop in Gleisdorf, Styria, the ‘Slender Styrians.’ “The idea behind the design was maximum simplicity while retaining the usual symbolic shapes and height differences … ,” as he describes the underlying concept.

The woods he used—bleached boxwood for the White side and alcohol-stained Castello wood for Black—echo the colours of the Styrian flag: white and green. Thanks to their brass weights and broad bases, the pieces stand firmly on the chessboard. The two sides are finished with white and black leather soles. The chess pieces are elegant and enchanting: instead of a crown, the king carries his Reichsapfel (orb) in a chalice-like blossom; the queen, bishop, and rook open upward at their tops toward the sky. Indeed, all the pieces seem to reach heavenward thanks to their slender design. The knights, finally, are shaped as classic double-headed knights, reminiscent of chess sets from the Renaissance or early Baroque. In our opinion, these chess pieces are unsurpassed in their beauty.

Renowned Australian woodturner Mike Darlow is internationally known as the author of several foundational books on woodturning. Thousands of turners around the world have learned from him.

In 2004, he published “Turned Chessmen” as the fifth volume of his now eight-volume Woodturning book series. Holger Langer wrote in his review: “The book gives a lot of background information on the various pieces’ symbols and on technical terms. Very useful!”

The book is regarded as a comprehensive guide to the making, history, and design of turned wooden chess pieces. It includes, among other things, a detailed history of chess pieces, a gallery of contemporary chess sets by modern turners, as well as several detailed drawings for complete chess sets that turners can replicate or modify.

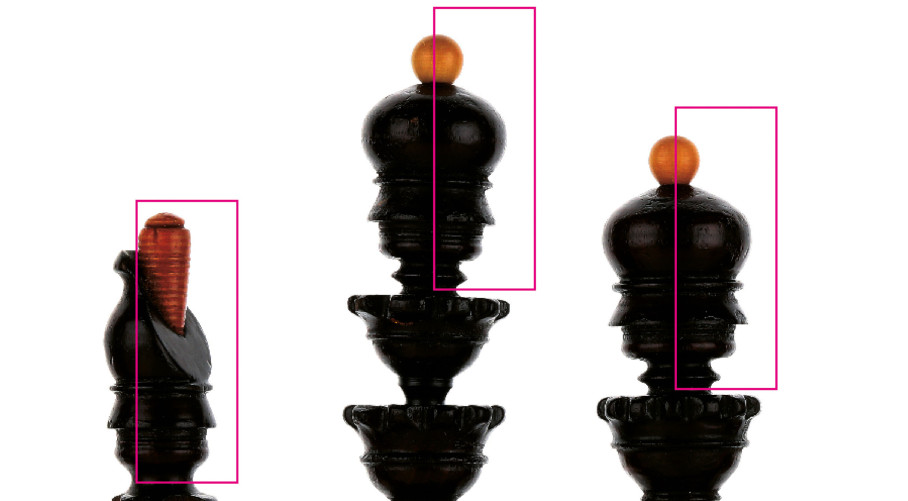

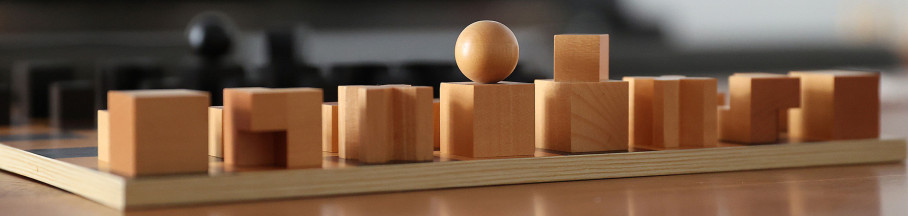

One of the designs presented is the “Lopez” set, developed by Mike Darlow himself. It is intentionally minimalist, yet stands out through its consistent shaping, impressive size (the king stands well over 12 cm tall), excellent distinguishability of the individual pieces, and outstanding stability. The name “Lopez” honors Ruy López de Segura, the Spanish priest and pioneer of chess theory, whose opening, the “Spanish Game,” is one of the oldest and most popular in chess.

The pieces are elegantly turned, with clear contours that emphasize the “traditional” symbolism, largely inspired by Staunton designs. The bodies of all pieces are turned from the same type of wood, while the color distinction appears only in the upper sections (light wood vs. dark wood). In this way, the set showcases the beauty of three different timber species.

The set is an absolute joy to use and feels wonderful in the hand.

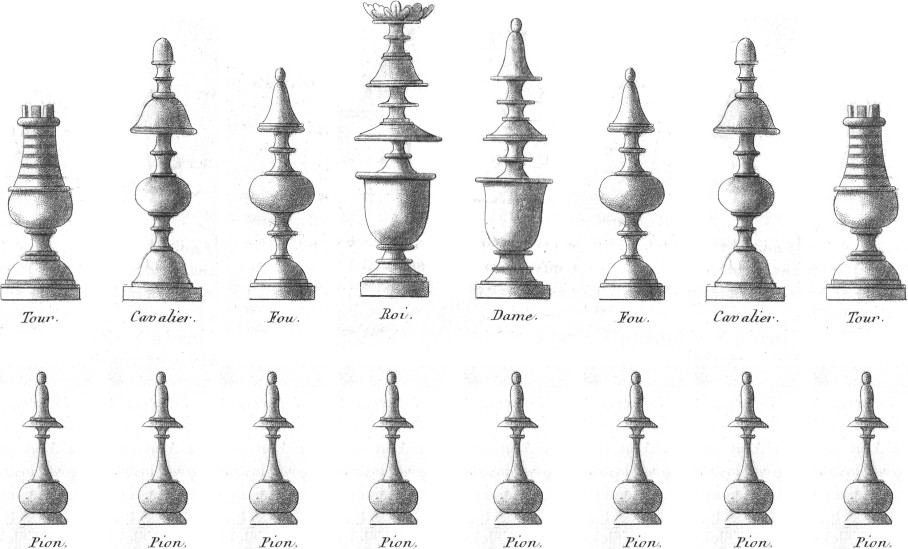

Between 1751 and 1772, the "Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers" by Denis Diderot and Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert was published in France.

The Encyclopédie was not just a neutral collection of knowledge – it was a programmatic work of the Enlightenment. It aimed to gather, critically examine, and spread knowledge in order to transform society. Many articles in the Encyclopédie were intentionally provocative. They questioned religious dogmas, political authority, and the arbitrariness of monarchies. This made the work a mouthpiece for Enlightenment thinking and the push for greater freedom.

Diderot and d’Alembert set new standards for organizing and linking information through carefully structured articles and cross-references. They emphasized that knowledge is not static, but evolving and to be shared with everyone. The work had a huge influence – it shaped the intellectual climate before the French Revolution and helped lay the groundwork for a more reason-based and rights-oriented society. The Encyclopédie was not the first encyclopedia, but it was the first with a clear philosophical and social program. It stands for the ideal of free, progressive thinking – a milestone in European intellectual history.

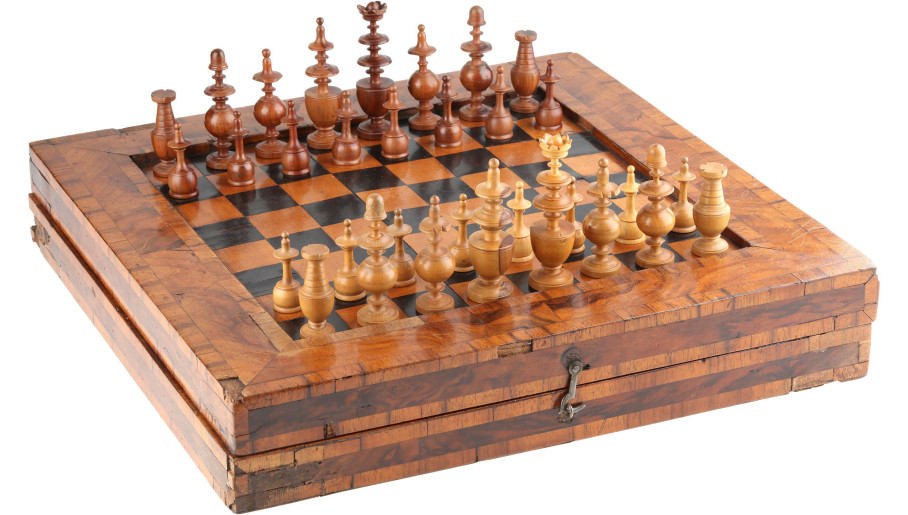

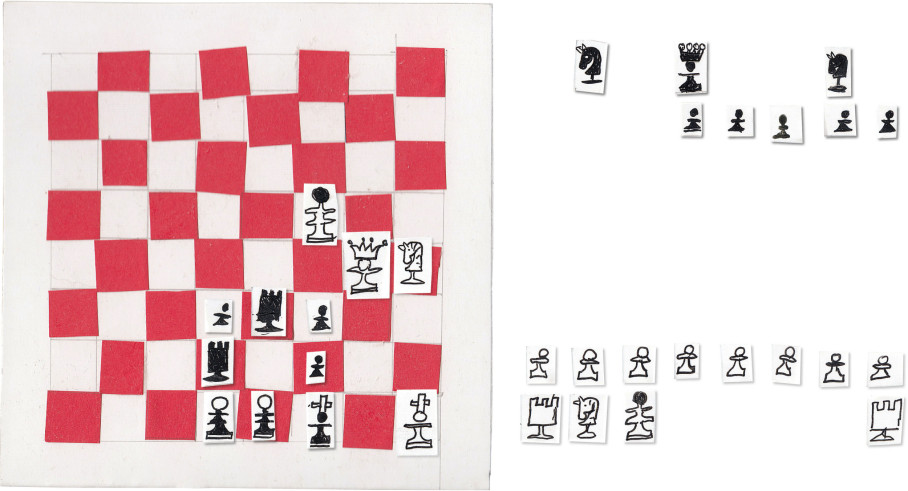

Unlike earlier encyclopedias, which often focused only on scholarly knowledge, the Encyclopédie also included practical trades and craftsmanship. This reflected the ideal that all useful knowledge – not just philosophy or theology – was valuable. Interestingly, it seems that chess also found a place in this wide-ranging collection. Of particular interest to collectors of antique chess pieces is a copperplate engraving from around 1772. Robert Bénard, a prominent engraver responsible for many of the encyclopedia's illustrations, is believed to have created this depiction of chess pieces.

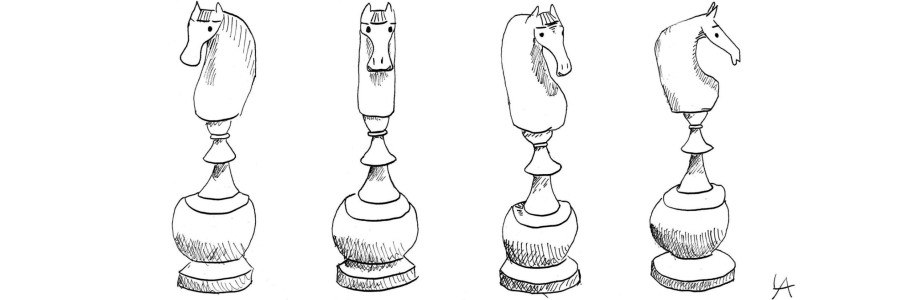

Crochet Knights from Lina Altrichter's workshop. Crochet is often underrated. The art of creating two- or three-dimensional objects by interlacing loops of yarn or thread gained popularity during the Biedermeier period. The knights have removable bridles. Knight height 7 cm

Without the French Revolution of 1789, the Biedermeier period would never have come about. What does that mean, exactly? The revolution threw the balance of power in Europe into chaos, and as a result, the Napoleonic Wars raged from 1792 to 1815. When Napoleon abdicated in April 1814 and was exiled to the island of Elba, the victorious powers met in Vienna for the so-called Congress of Vienna to discuss the political reorganization of Europe. But before the congress had even concluded, Napoleon escaped from Elba, rallied the remnants of his Grande Armée, and reignited the conflict.

Austria’s foreign minister, Prince Metternich – who chaired the congress – was just as shocked by the news as the hundreds of appointed delegates from Russia, the United Kingdom, Austria, Prussia, and many other European powers. This led to Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and his final exile to the remote British island of Saint Helena.

Still, the shock of Napoleon’s unexpected return ran deep. Metternich responded by turning the page to a new chapter in European history – one that aimed to restore absolute monarchical authority. His goal was to ensure political power remained exclusively in the hands of the nobility, to prevent any violent takeover by opposition groups, to reject constitutional government outright, and to return society to its pre-revolutionary state.

Under what became known as the Metternich System, civil liberties such as freedom of the press, speech, and assembly were strictly suppressed. In response, many citizens retreated into the privacy of their homes to avoid confrontation with the state. It was also a golden age for domestic music-making. The stay-at-home, non-revolutionary citizen became the archetype of the politically passive, hard-working, and somewhat narrow-minded middle-class man – jokingly referred to as the "respectable Mr. Meier," or Biedermeier.

Perhaps Biedermeier chess pieces really are a little fragile slice of an idealized, peaceful world …

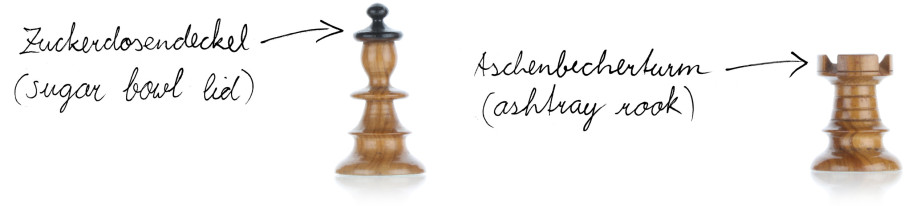

From an artistic perspective, the first decades of the 20th century were also a time of simplification. Since 1910 (Kandinsky) there has been conscious abstraction and stylization. Movements such as Art Déco and Constructivism, Rayonism, Orphism, Cubism and Futurism were almost commonplace. It would therefore be easy to dismiss the “Deutsche Bundesform” as a Nazi work. If you look at the beauty of the stylization and then use high-quality materials such as horn, then you are suddenly faced with elegant Art Déco chess pieces.

The secret of porcelain production came to Vienna in 1718 with Claudius Innocentius du Paquier. There he received the privilege of producing porcelain from Emperor Charles VI. The Porzellangasse in Vienna's 9th district is still a reminder of this today. In 1744 the manufactory came into imperial possession. With the collapse of the monarchy, the company was re-established in 1923 at a new location: in Vienna's Augarten. At the same time, the company was known as the “Porzellanmanufaktur Augarten”.

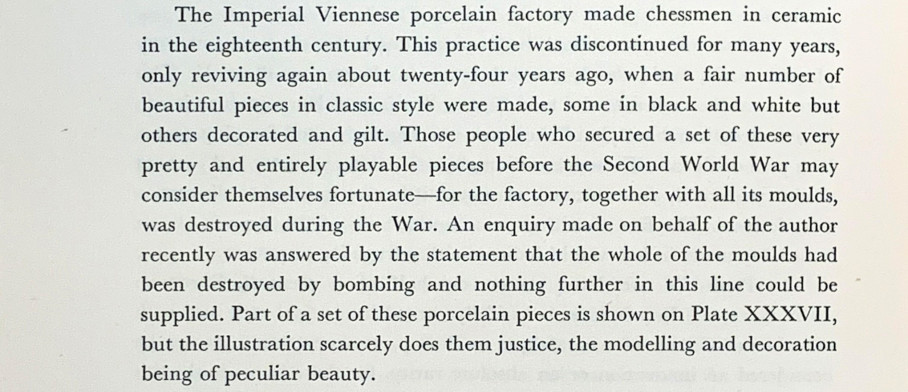

Chess collector Alex Hammond wrote in “The Book Of Chessmen” in 1950: “The Imperial Viennese porcelain factory made chessmen in ceramic in the eighteenth century. This practice was discontinued for many years, only reviving again about twenty-four years ago, when a fair number of beautiful pieces in classic style were made, some in black and white but others decorated and gilt.”

When asked about this, the art historian Claudia Lehner-Jobst from the Augarten Porcelain Manufactory contacted me. Claudia Lehner-Jobst: “As far as I know, the imperial factory did not produce any chess sets in the 18th or 19th centuries, although games of all kinds were an important part of court life and there are some very nice tins with playing chips from the Baroque period.” A chess set was added to the product range as early as 1924. (see photos). The playful Art Déco design comes from the artist Mathilde Jaksch, who created numerous, some very popular, designs for Augarten. Very little is known about Mathilde Jaksch; she was born in 1899 and received artistic training in Vienna and Gmunden. At this point we would like to thank Claudia Lehner-Jobst for her help.

Hammond continues in the book: “Those people who secured a set of these very pretty and entirely playable pieces before the Second World War may consider themselves fortunate—for the factory, together with all its moulds, was destroyed during the War. An inquiry made on behalf of the author recently was answered by the statement that the whole of the moulds had been destroyed by bombing and nothing further in this line could be supplied.” The chess set can still be bought at Augarten today, so it is obvious that after the moulds were lost, they had to have been remade. Our inquiry as to whether the post-war pieces were modeled after the original chess pieces or whether only a mould was made from existing pieces has not yet been answered. This is interesting because the post-war chess pieces in the latter case would have to be significantly smaller than the chess pieces from 1924 due to the shrinkage during firing (about 20%!).

Addendum

We have now found in Donald M. Liddell's "Chessmen" from 1937 both a funny remark about the Augarten chess pieces from 1924 and an important reference to the chess pieces made by the Imperial Viennese porcelain factory in the 18th century mentioned by Hammond.

The funny comment: “The Viennese Imperial China Factory was revived in 1926, and has turned out some typical little Viennese figures, very beautiful, though we may question whether a bathing-beauty Bishop has any place on a battlefield.” (Chessmen, page 68)

The important note: “The Alt Wien works imitated the Meissen chessmen, making them a little smaller than the originals, using the beehive potter’s marks. (ibid)

It seems that in the 18th century the Viennese Imperial Factory only moulded the chess pieces produced by Meissen, so that – after the firing – shrunken versions of the Meissen figures emerged. In this case, these chessmen would be pirated copies. It would be interesting to know whether there are any chess collectors among the readers of these lines who have such chess pieces (in the shape of the Meissen figures but with the beehive of the Austrian Porcelain Manufactory) in their possession. We would be pleased to hear from you.

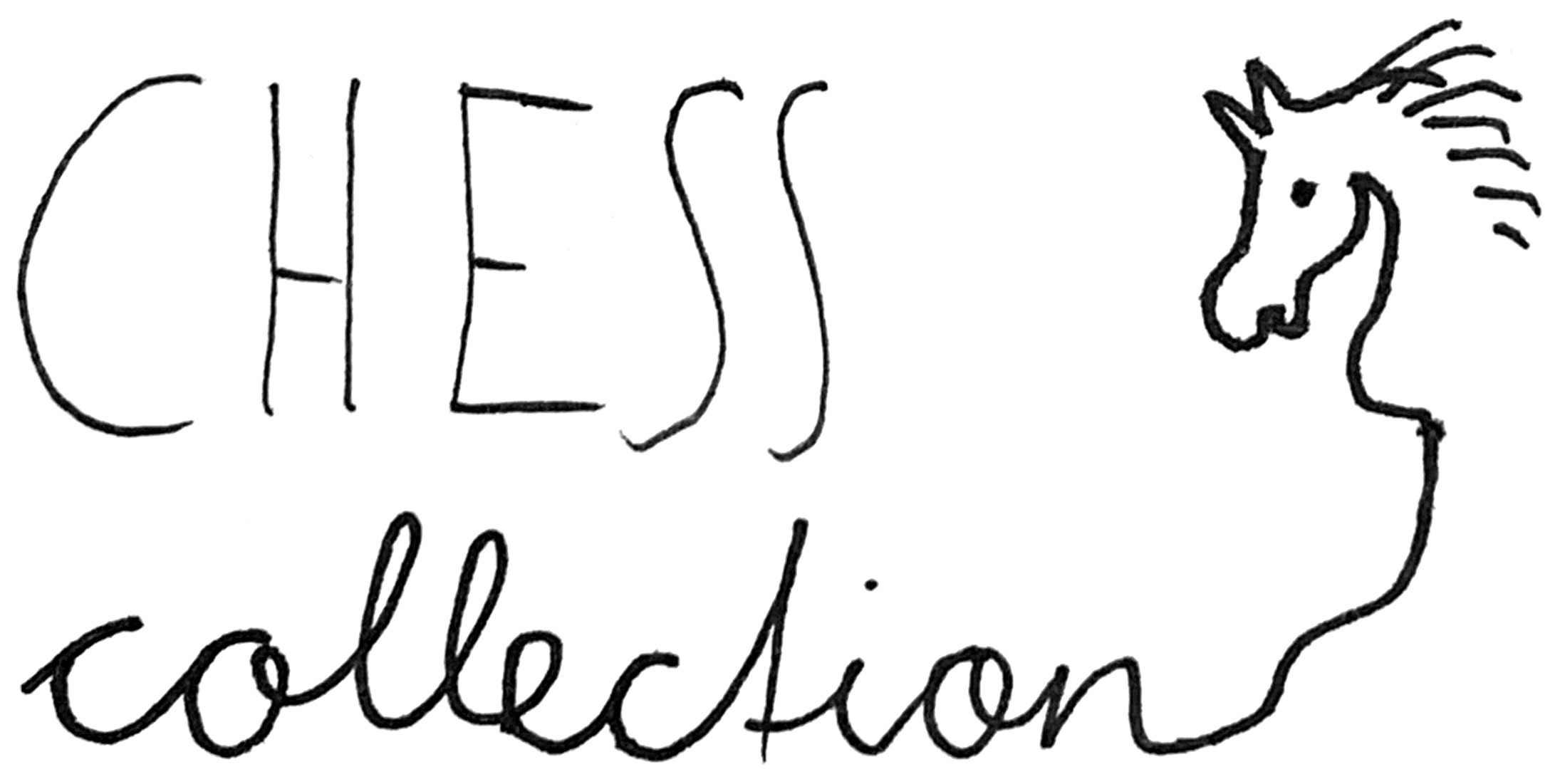

Nicholas Lanier (1954–2019) noted on his website: “The St. George chess pieces got their name from the St. George Club, founded in 1843 on the street of the same name in central London, which chose these chessmen as part of the club set. (…) As a result, St. George sets were made not only by the leading manufacturer Jaques, but also by other chess piece turners, such as Lund, Fisher, Hastilow, Calvert, Ayres, etc., sometimes in unusual and opulent versions in ivory and mixed materials. St. George sets were also made in very cheap variations for the toy market – also by Jaques. Interestingly, St. George sets were also produced in Germany from the middle of the 19th century … .”

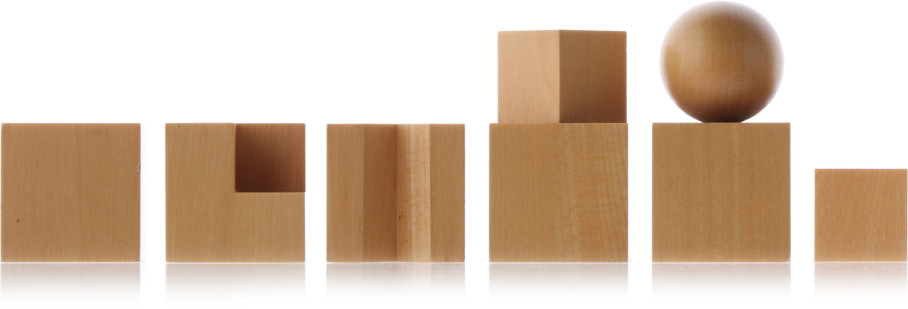

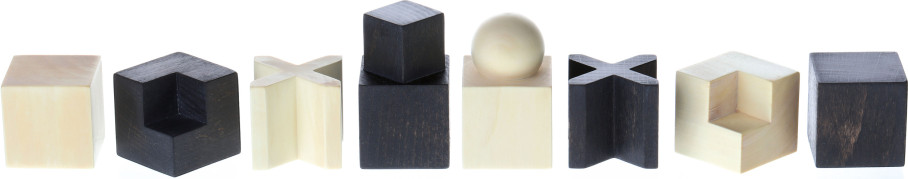

At the latest with Josef Hartwig in 1923, strict geometry found its way into the game of chess. Hartwig was a master craftsman of wood and stone sculpture at the Bauhaus in Weimar. You don't have to think it's nice, but it's reasonably consistent (although there are enough arguments that only the rook and bishop are consistently shaped).

There is this surreal short story by Guillaume Apollinaire (or was it Louis Aragon?) in which a sculptor decides to create a sculpture out of air. At first glance that may sound difficult, but the inventive and imaginative sculptor in the story simply dug his desired figure into the earth. The removed soil was gone, and the figure he envisioned appeared as a hollowed-out form in the ground.

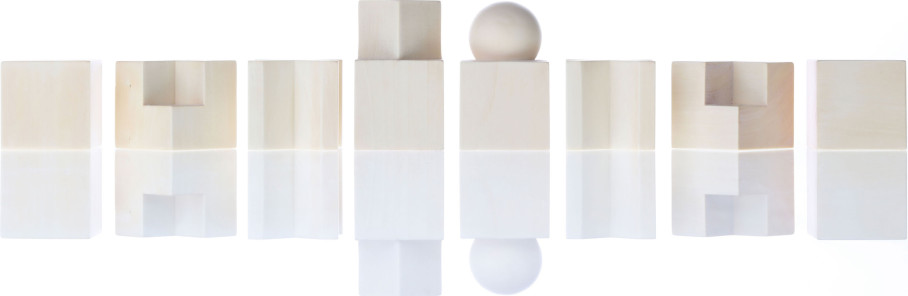

This story came to mind when we first saw Helfried Puhr’s interpretation of the Bauhaus chess pieces. Unlike Josef Hartwig, who ultimately seems to have aimed for modern serial production, Helfried set himself a very different challenge:

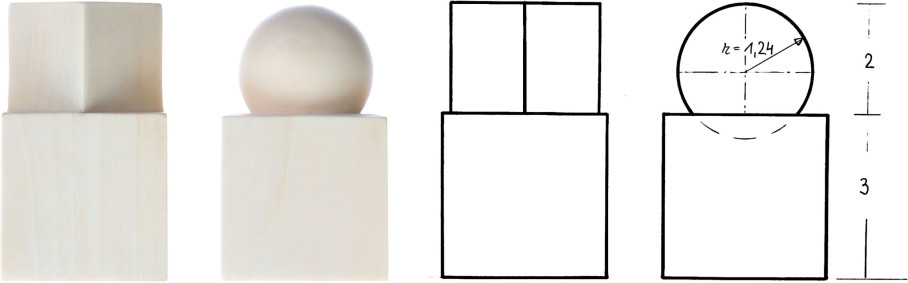

“Except for the size of the queen’s sphere (see the discussion at the Schaakmuseum), the dimensions are fairly easy to determine, and the amount of material used is also manageable. As an additional challenge, I therefore decided to shape each piece from a single piece of wood, thereby completely deviating from the core concept of the simplest possible manufacturing — Hartwig may forgive me.” That’s what Helfried wrote to us in November 2025.

Now, this is anything but simple. Just consider that, for example, a rotating milling head always moves around a single axis — which means that a true corner, such as the one required for the knights, cannot be produced mechanically.

It is a fascinating idea: all the pieces initially share the same body when it comes to their square base, and they are then cut to different lengths. Only through the removal of wood do distinguishable forms emerge — forms that then correspond to Hartwig’s design concept. This subtractive process is what brought back our memory of the surrealist sculptor …

The “discussion at the Schaakmuseum” that Helfried mentioned concerned, on one hand, the size of the queen’s sphere, and on the other, the degree of its “appearance” above the cube, if one may put it that way. Imagine the sphere rising — like from a lake or an ocean — out of the cube. How far upward should it emerge? The manufacturer Naef apparently opted for a bold version in which the sphere fully rises out of the cube and essentially rests on top of it. That the queen thus overtops the king already suggests that this solution may not be ideal.

Joost van Reij was kind enough to photograph the original Bauhaus set exhibited in Nuremberg for Helfried. In Joost’s forum, Helfried writes: “Thank you for the picture from the German National Museum. In the meantime I have finished my version of the Bauhaus chessmen, and I think the measurements/relations are approximately the same. The big cube 30 mm, the small cube 20 mm, and the volume of the queen’s sphere the same as the volume of the small cube.”

Helfried used bleached spindlewood (Euonymus europaeus) for the white pieces and blackened beech for the black pieces, with a hard-oil finish. Thanks to this surface treatment, the elegant chess set closely resembles the traditional names of the two sides: “White” and “Black.” As a final touch, Helfried also created a fitting box to house the pieces.

Here we are pleased to present a chess set that was made 2024 by the Styrian amateur wood turner Helfried Puhr. Helfried's intention was to create a model based on the famous Lasker-Schlechter chess set from the beginning of the 20th century.

In February 2024, Helfried wrote: "There is a technical problem in the production of the crowns of the king and queen (…). In my opinion, the original ends were made on a Passig lathe. Passig lathes were machines whose spindles regularly moved back and forth during rotation, towards and away from a fixed tool. The cutting edge of the tool was shaped accordingly, as a "shaping iron". As I cannot make the spindle on my lathe "wobble", I am trying to use a device that brings a self-made shaping iron in a suitable shape to the rotating workpiece at intervals.

I know that replicas of the Lasker-Schlechter chess pieces also come with milled ends on kings and queens, but I'm stubborn, either original or nothing.”

Ultimately, Helfried managed to modify his machine accordingly. The chip removal was much lower than 5/100 mm per revolution. He also had to convert his machine to manual operation. Long working days were the order of the day...

Some time ago we came across a delightful little bone chess set with nice knights. The inscription on our chess box says: BONE STAUNTON SET RED/WHITE. STIRLING COMPANY. CA. 1880. KING 58 mm / 2 ¼". COMPLETE. ORIGINAL BOX. When we asked Chuck Grau about it, he said: “(…) you might want to compare it to some Horn-McCrillis bone pieces. I’m pretty sure this Stirling is not the Sterling Furniture Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan (…)”. And in fact, the Sterling Furniture Company only existed since 1924.

Well, we compared. The US chess piece manufacturer HORN was founded in 1846 and was based in New York. They very confidently saw themselves as the “National headquarters for American made chessmen and chess boards.” Since Horn primarily produced stationery, and according to Duncan Pohl (page 46) there is evidence that McCrillis Inc. supplied cribbage boards, it is reasonable to think that McCrillis may have been the true producer of chess sets for Horn.

Presumably in the 1930s, a wood turner in the USSR set to work on a design for a chess set. A carver (or did the wood turner also do the carving himself?) came to his aid and took care of the four knights. The result was an interesting chess set, which today boasts a wonderful patina. The knights look like pieces of modern art and are reminiscent of the Cubist style. The bishops seem exceptional, as do the rooks, with their enormously broad base. Chuck Grau, operator of the Facebook group Shakhmatnyye Kollektsionary, points out that individual pieces such as the queen and king are reminiscent of chess sets from the Vsekokhudozhnik artel. In fact, we owe all the information about this set to him and his group.

Little is known about the true origin of these chess pieces. They were actually distributed by the American Chess Company, based in 150 Nassau Street, New York. But were they also manufactured by the ACC? Rumors suggest they could have been imported from the Old World. But who would be responsible? When we first saw these pieces, our association was Russia.

Similar chess pieces were used in the famous Cambridge Springs tournament in 1904. Čigorin allegedly complained about the poor quality of the pieces (given the high price they fetched at the auction after the tournament). The chess pieces shown here are, in any case, exquisitely crafted. The game boards used in the tournament were supposedly made of cardboard …

Incidentally, we are convinced that they are real American chess pieces. Why? The economically busy USA in the second half of the 19th century had enough craftsmen to have such chess sets made on site. An overseas import would not have made the chess pieces cheaper.

Assuming the American Chess Company would have signed a manufacturer in France: In all the differences to the aesthetics of the generally usual Régence pieces there, a manufacturer would probably have only embarked on taking care of special forms on customer requirements if a larger order quantity had been agreed. This contradicts the fact that only a few copies of the ACC chess pieces are known.

In addition, the Americans have developed so many formally independent achievements that they can be granted these wonderful forms of clear conscience.

In the beautiful Austrian state of Carinthia, metal chess pieces were recently offered for sale. They bear a strong resemblance to the pieces produced around the turn of the century by the Württembergische Metallwaren Fabrik (WMF), as shown, for example, by Holger Langer on his website.

Apart from the king and queen, nearly all of the Carinthian pieces closely resemble those of the WMF chess set.

Could this perhaps be a prototype? Was WMF originally intending to design the queen and king in a more elaborate fashion, but then abandoned that idea during the prototype stage? The undersides of the chess pieces are rough and appear completely untreated. Moreover, the pieces are not stamped, as is usually the case.

Collectors have come to refer to chess pieces seen in photographs from the 1920s as “Smyslov” pieces, because the young Vasily Smyslov was once pictured with a set of this kind. On our example, fine white felt fibres have become caught in the early Soviet lacquer — a finish that seems to have worked as both varnish and glue.

The “Smyslov-style” is instantly recognisable by the unconventional column-form of the pawns, bishops, queen and king. Unlike typical columns that flare at the base and taper toward the top — just as every tree does — these pieces boldly begin narrow at the bottom and widen as they rise. Very elegant indeed! By contrast, the rook and the base of the knight adopt a dam-like shape, as if built to withstand any flood. And as a special flourish, the knights in this set are carved with striking individuality.

The woodcarving tradition of the Erzgebirge has its roots in mining culture. Miners who found leisure time after completing their work took up wood and carving knives to create small works of art. After the decline of mining, this tradition became an important source of income for many families in the Erzgebirge. In the 20th century, woodcarvers also turned to the theme of chess. The chess pieces shown above are especially expressive and carved with a confident hand.

What is beautiful and what is not can only be decided by each individual. Fortunately, there is no measurable truth to dictate it. What we find pleasing or displeasing is shaped by the time in which we live, by our upbringing, by our craftsmanship, and, of course, by the materials at our disposal. Beauty, in the end, is a matter of perception, unique to each person and each moment.

Let Albrecht Dürer have the last word on beauty: I grant that one may both conceive of and make a more beautiful image, and may set forth its good and natural cause more intelligibly to reason than another; yet not so far as to conclude that it could not be more beautiful still, for such knowledge does not enter into the mind of man. God alone knows this; and he to whom He reveals it, knows it also.